Chopin: Etudes

“Oh, they are all dreadful.”

Vladimir Horowitz’s admissions about the twelve Etudes op. 10 and the twelve of op. 25 by Frédéric Chopin, all of which he found dreadful, or to be precise, dreadfully difficult, are both revealing and disarmingly frank: “For me, the most difficult is the one in C major, op. 10/1. I cannot play it, and the other one in C, op. 10/7, is no better. And I can’t really play the one in A minor op. 10/2 properly.” – Even if his outspoken confessions contain more of a degree of playfulness than some similar statements made by the famous Chopin performer Arthur Rubinstein, it is indeed the case that well into the 1970s the Chopin Etudes were deemed so technically difficult that it was the norm for any pianist not to play them all in public or record them in one go, but to play them one at a time like Horowitz and Rubinstein. That said, the musical ranking of the individual works has always been a matter of controversy. The fact that the complete recordings by the few pianists whose names are still familiar – Backhaus, Cortot, Arrau – are from artists who all share an interpretational style and choice of repertoire that is decidedly serious in approach could be an indication that these exponents, who after all had the necessary technical skills at their fingertips, were also concerned with the great musical context.

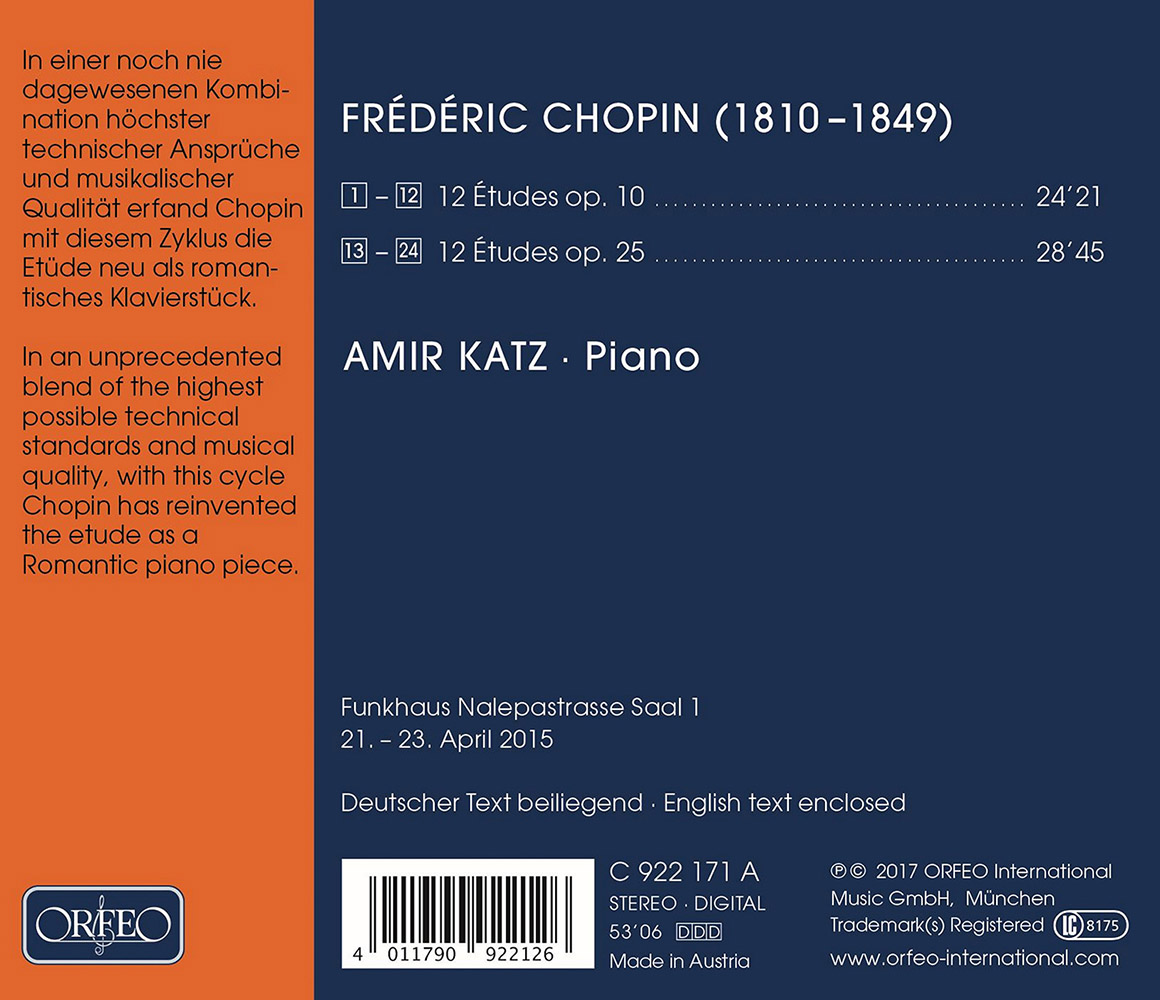

Times have changed since then, however, and the technical standard expected today of a young pianist has risen relentlessly, while at the same time much has happened in the musical sphere when it comes to Chopin interpretation. Today, all of the Polish genius’s works have increasingly come to the fore for their uniqueness and their unsurpassed quality, with the result that more and more pianists are daring to tackle the fearsome 24 Etudes – at least in the studio. In preparation for the studio recording, Amir Katz sought audience approval by performing the works frequently and to acclaim in concert. As with previous projects, he wanted to take a holistic approach to the pieces, beginning with the famous “bracket effect” of the first and last pieces in C major and C minor, both of them closely related to the first two pieces of Bach’s “Well-tempered Clavier” and to the last etude that then modulates back to C major – which ultimately brings the work full circle in terms of tonality. What is more, in his assiduous study of the sources on early performance practice, Amir Katz has found divergence in the earlier (faster) original tempi, especially in the slower movements, and exact tempo correspondences between various pieces. Finally, the young virtuoso proves his credentials in these masterworks with a flawless clarity that is more than equal to its stylistically refined, artistically “simplified” neo-Baroque echoes.