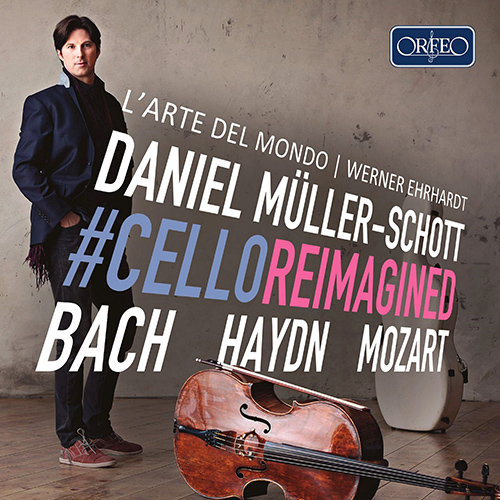

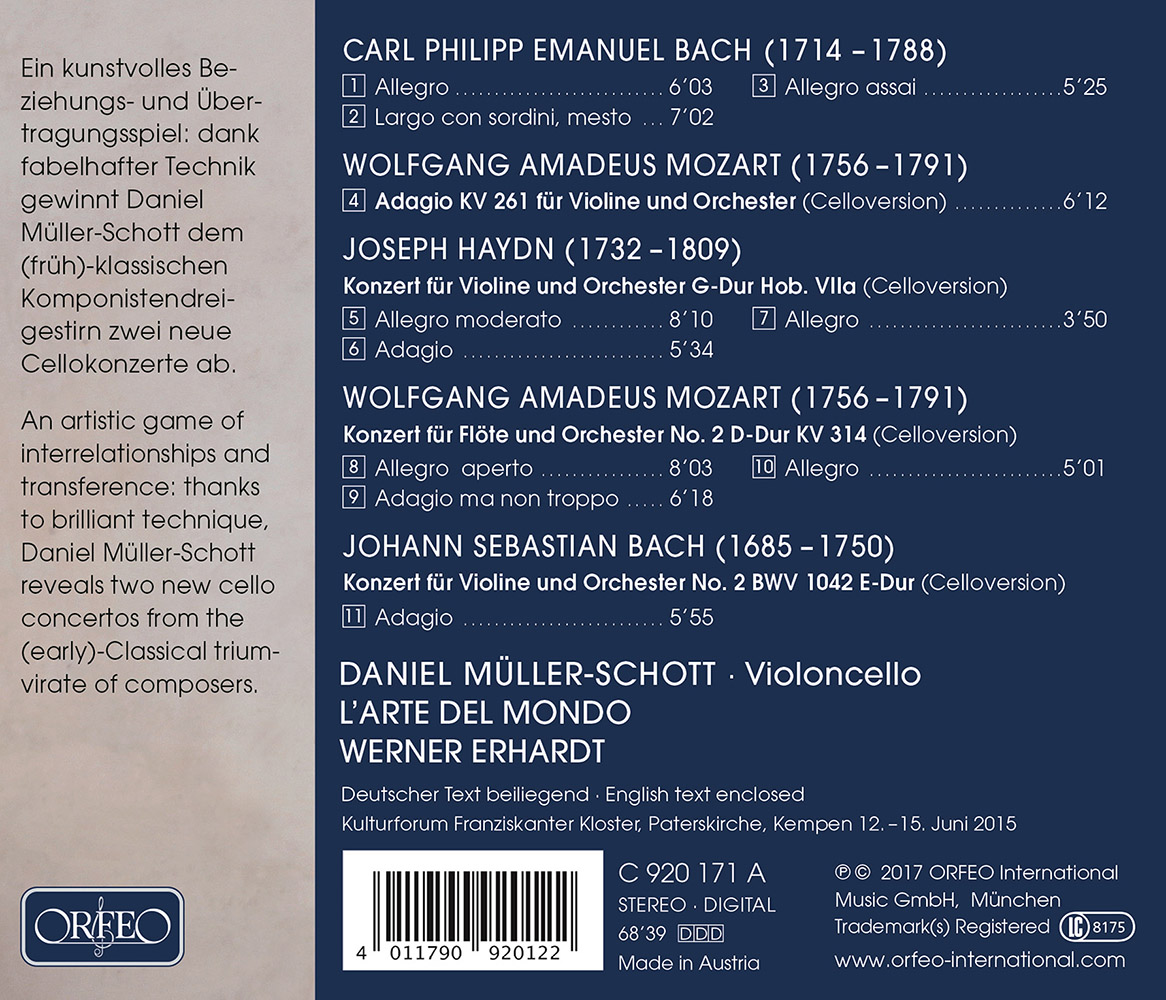

CelloReimagined

Two new cello concertos from a generational triumvirate

On his new recording, the musician, who always demonstrates a verve and lively curiosity in his programme works, brings together three composers for his instrument to form a musical triangular relationship that is fascinating to experience and only possibly thanks to some nifty cross-fertilisation. The consequent easy accessibility and good audibility form a charming contrast to the works’ all but easy playability.

For a start, the intertwining and superimposition of successive generational is charming in itself: Johann Sebastian Bach’s son, born in 1714, was perhaps the greatest composer of his generation; the essential founding father of the Classical era and creator of significant music genres, born in 1732; and finally, the child prodigy born in 1756. The dates of their deaths, however, then seem to skew the chronology: Mozart died in 1791, just three years after Carl Philipp Emanuel, whereas Joseph Haydn lived another 18 years.

CPE Bach made a significant contribution to establishing the piano concerto genre and arranged three such works for flute and – all of them predictably virtuosic – for the cello, one of which can be heard on this recording. Haydn on the other hand wrote, as is well known, the first and sadly the only great “Viennese Classical” cello concerto, which Daniel Müller-Schott naturally plays often and has already recorded (C080031). He also composed piano and violin concertos, one of which appears here in an arrangement for cello and is technically very demanding. Although the early consummate master of the piano concerto genre sadly did not write a cello concerto, Daniel Müller-Schott, in the tradition of Emanuel Feuermann, has attempted to imagine what Mozart’s Oboe Concerto, which the young composer later arranged himself for flute, would sound like on the cello. In the process, he demonstrates in a staggering manner the typical way in which Mozart transcended the borders of genres for solo concerto: in truly operatic performances and much more, all so artfully achieved and performed that the instrument being played is simply not uppermost in the listener’s mind, let alone the one for which the work was originally composed.

What is more, the experiment of repertoire expansion through transference succeeds in this instance not least thanks to the skill and lively, infectious musicality of the L’Arte del mondo ensemble under the direction of Werner Erhardt, who are clearly all very much at home with this sort of music.