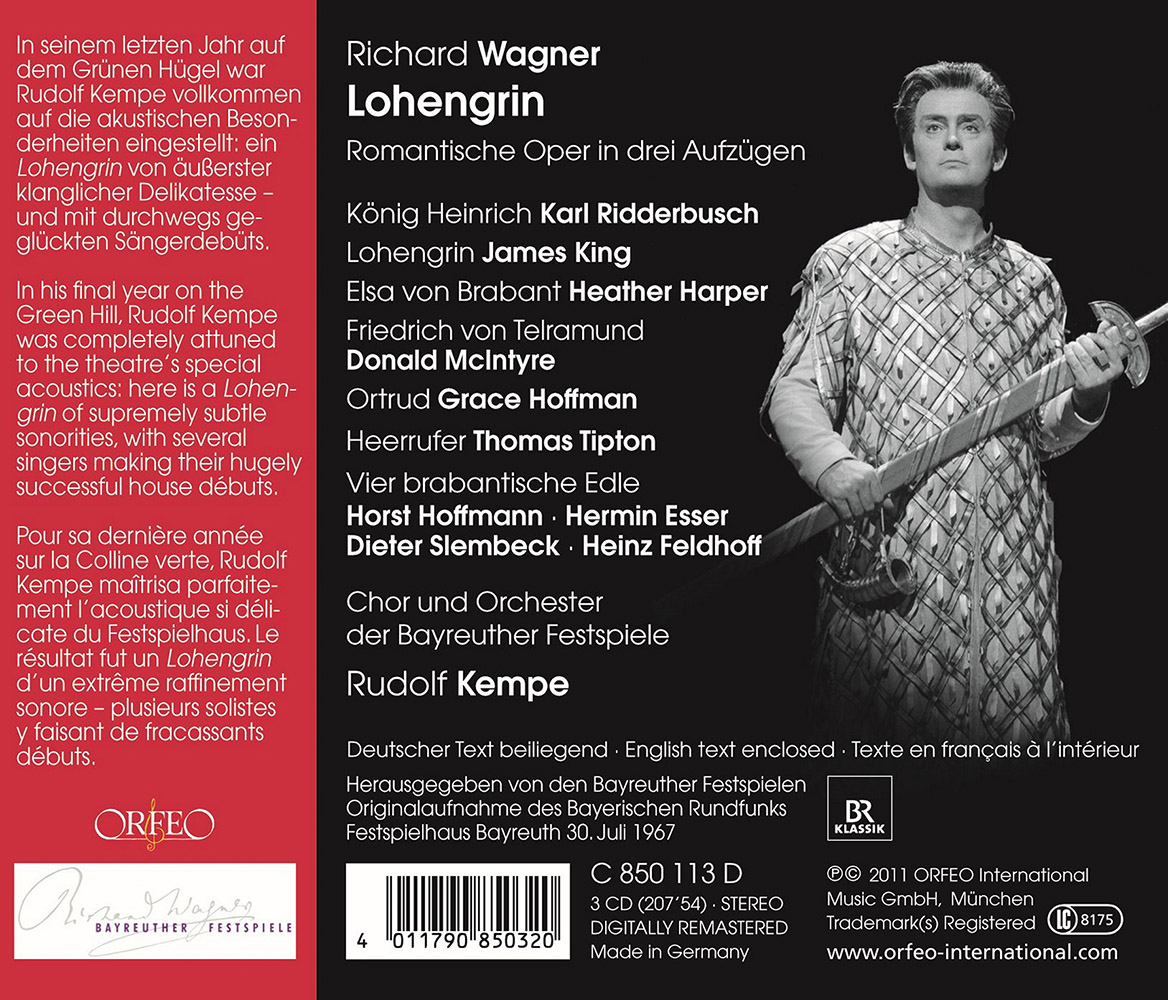

Composer(s):

Conductor(s):

Orchestra(s):

Artist(s):

Genre(s):

Opera

Period(s):

Romantic

Label:

Orfeo

Catalogue No:

C850113D

Barcode:

4011790850320

Release Date:

11/2017

Available Format(s):

CD

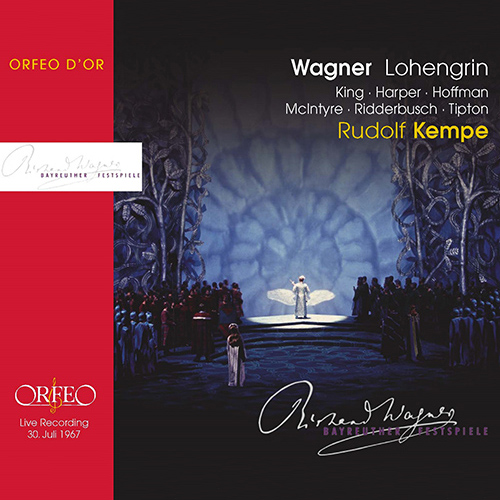

Richard Wagner: Lohengrin (Bayreuth, 1967)

Lohengrin

2. Act I Scene 1: Hört, Grafen, Edle, Freie von Brabant! (Herald, Brabantines, The King, Saxons)

04:35

5. Act I Scene 2: Einsam in trüben Tagen hab' ich zu Gott gefleht (Elsa, All The Men, The King, Friedrich, Brabantines)

07:21

7. Act I Scene 2: Wer hier in Gotteskampfe zu streiten kam (Herald, All The Men, Friedrich, Elsa, Ladies, First and Second Chorus)

05:37

10. Act I Scene 3: Nun höret mich und achtet wohl (Herald, All The Men, Lohengrin, Friedrich, The King, Elsa, Ortrud, Ladies)

02:30

11. Act I Scene 3: Mein Herr und Gott, nun ruf ich dich (King, Elsa, Ortrud, Lohengrin, Telramund, Chorus)

05:18

12. Act I Scene 3: Durch Gottes Sieg ist jetzt dein Leben mein (Lohengrin, Chorus, The King, Elsa, Ortrud, Friedrich)

04:30

Disc 2

10. Act II Scene 3: Des Königs Wort und Will' tu' ich euch kund (Herald, Chorus, Four Nobles, Friedrich, Four Pages)

08:02

12. Act II Scene 4: Zurück, Elsa! Nicht länger will ich dulden (Ortrud, Elsa, Pages, Men, Women, Ladies)

08:38

13. Act II Scene 4: O König! Trugbetörte Fürsten! Haltet ein! (Friedrich, The King and Men, Ladies, Boys)

05:41

14. Act II Scene 4: Welch ein Geheimnis muß der Held bewahren? (The King and Men, Ladies, Boys, Friedrich, Ortrud, Lohengrin, Elsa)

05:10

Disc 3

1. Act II Scene 4: Mein Held entgeg'ne kühn dem Ungetreuen! (The King, Saxon/Brabantine Nobles, Lohengrin, Friedrich, Elsa, Ladies, Boys, Men)

07:15

11. Act III Scene 3: Tale of the Grail: In fernem Land, unnahbar euren Schritten …(Lohengrin, The King, Men, Women)

05:31

12. Act III Scene 3: Mir schwankt der Boden! Welche Nacht! (Elsa, Lohengrin, The King, Men, Women, Ladies)

01:24

Total Playing Time: 03:27:34