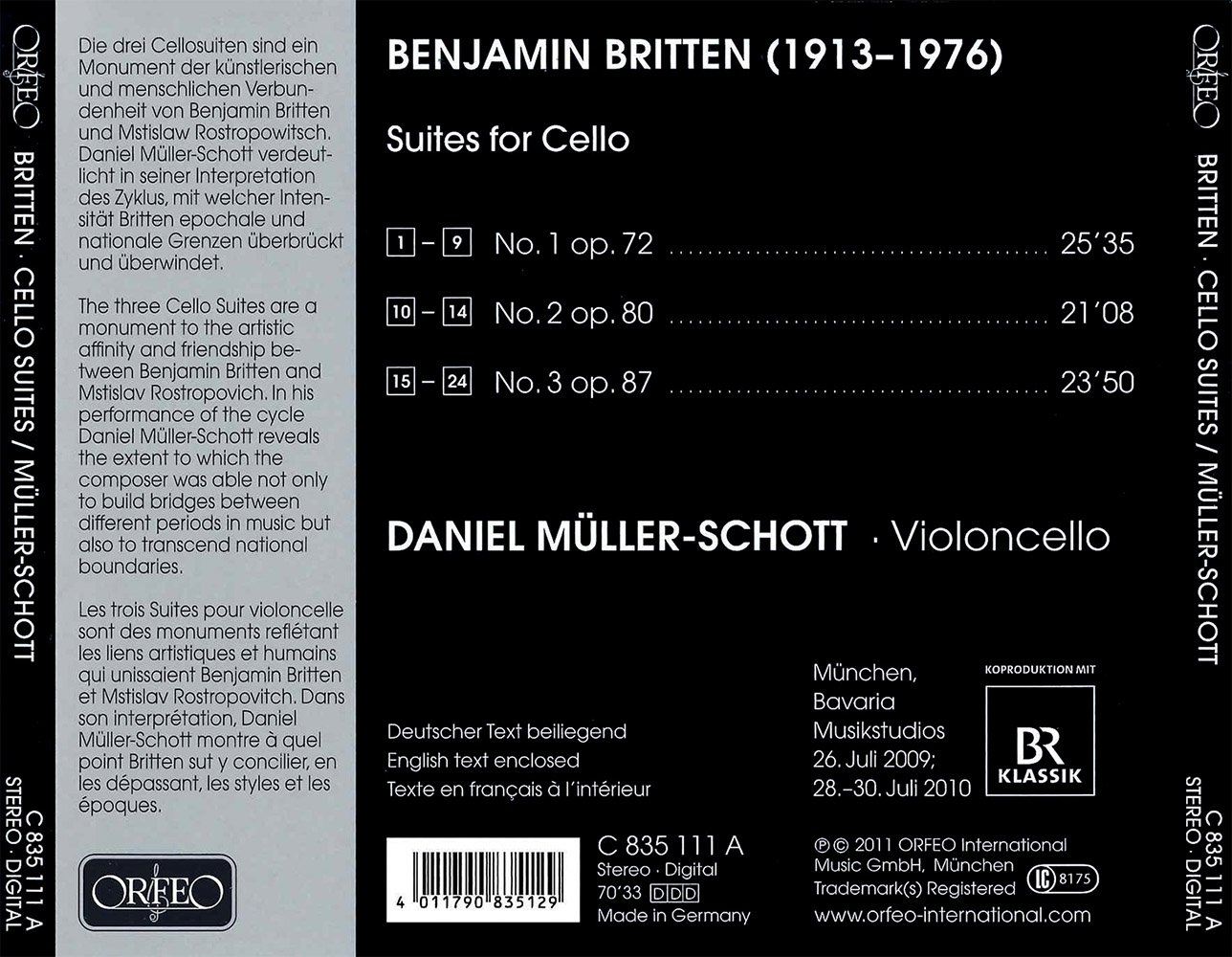

Britten: The Cello Suites

To be the dedicatee of a work by Benjamin Britten was a much coveted honour among 20th-century classical musicians. And for an artist to be the dedicatee of a whole series of works, then the musician in question – unless he happened to be Peter Pears – must have felt exceptionally blessed. Britten’s three Cello Suites are an example of such an exception. They were written over a period of barely a decade for Mstislav Rostropovich, and it was he who gave them their first performances. They are generally regarded as three of the greatest and finest challenges ever to be set a cellist. Daniel Müller-Schott, who had an opportunity to study with Rostropovich, faces up to this challenge with great enthusiasm and superior musicianship.

Daniel Müller-Schott

Foto: MaiwolfThe First Suite contains stylistic and formal reminiscences of the Baroque, and Daniel Müller-Schott brings to it great nobility of tone, just as he refuses to be discouraged from striking a note of genuine emotionality in the Canto passages. That his artistry is also underpinned by astute analytical skills is clear from the rigour that he brings to the part-writing in the fugue and concluding Moto perpetuo. This ability to maintain an overview of a piece also pays dividends in the Second Suite, with its rhythmically and thematically carefully balanced design, including the final Chaconne – a form whose climactic possibilities Britten had already exploited to supreme effect when writing for the full orchestra in his opera Peter Grimes. In the final movement of the Second Cello Suite the composer had no hesitation in placing similar demands on a single instrument. It is almost a foregone conclusion that a performer capable of rising to this not inconsiderable challenge will also shine in the third and last of these suites.

Daniel Müller-Schott

Foto: MaiwolfAt the time of its first performance in 1974, Britten was already too ill to fulfil his promise to write six such suites. Daniel Müller-Schott captures the work’s valedictory character, with its reminiscences of Russian folksongs and the Hymn to the Departed, bringing a keen eye for detail to the writing and not only pin-pointing all its musical beauties but revealing the ways in which those beauties are refracted through the composer’s elegiac lens. Rarely can 20th-century works have been so atmospherically interpreted.