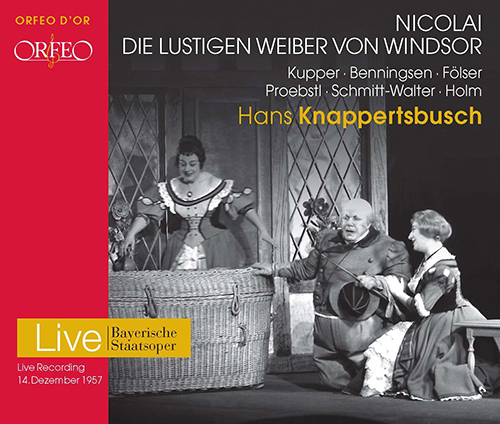

Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor

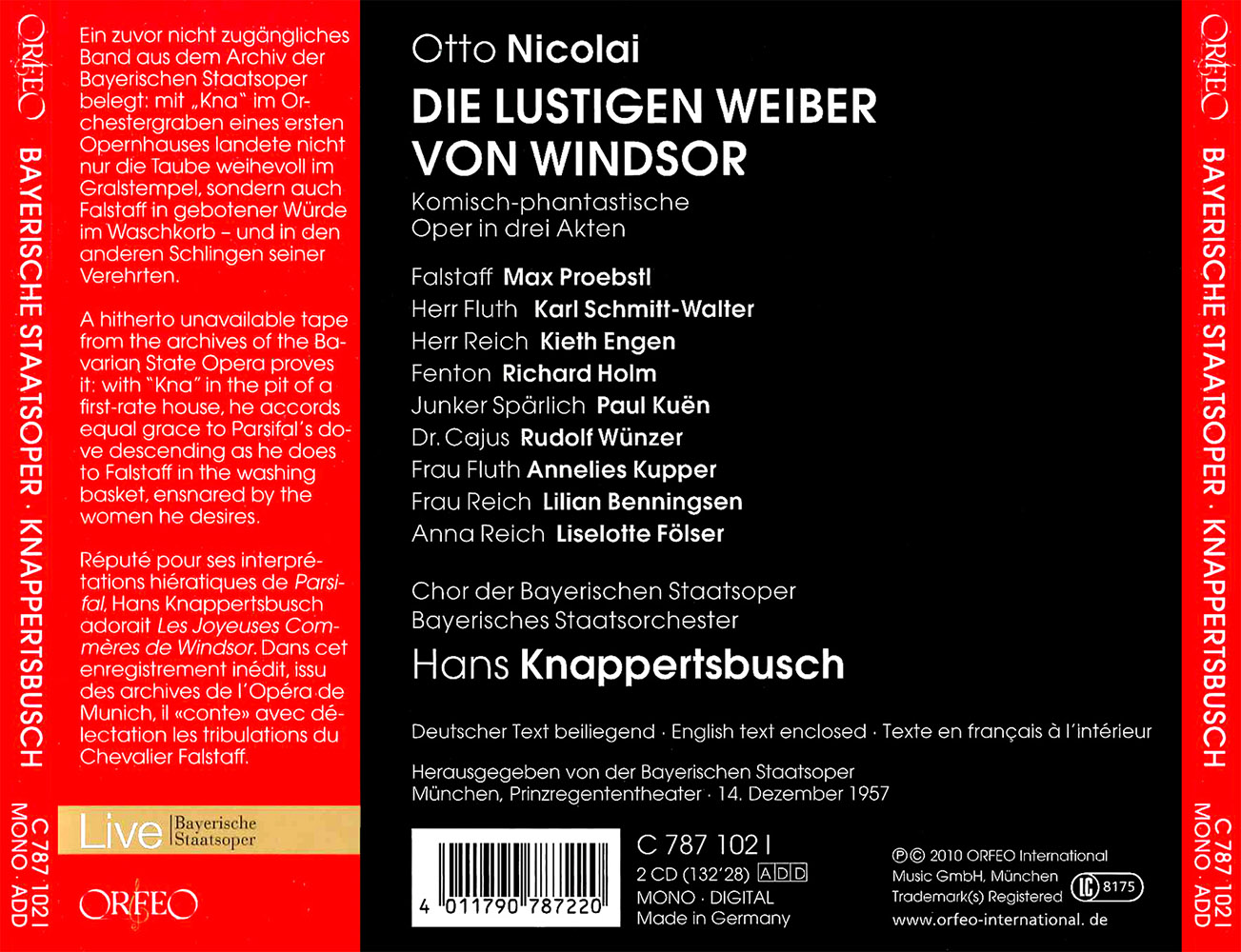

Hans Knappertsbusch conducted a far broader spectrum of repertoire – at least in Munich – than his unique reputation for Bruckner, Wagner and Strauss might let us suppose. Knappertsbusch even left his mark on the Romantic comic opera The Merry Wives of Windsor by Otto Nicolai (after Shakespeare). He conducted it at the Prinzregententheater, which became the legendary, temporary home of the Bavarian State Opera in the years after World War Two. The stark contrasts between the tender lyricism of the score and its earthy, humorous elements are savoured to the full by Knappertsbusch and the Orchestra of the Bavarian State Opera. Nicolai was born two hundred years ago on 9 June 1810. His different stylistic models all come to the fore here – such as Mendelssohn (whose teacher Zelter also taught Nicolai) and the Italian operas that Nicolai was able to get to know when he worked as an organist in Rome. At the Bavarian State Opera in 1957, the year when Knappertsbusch conducted the opening night of this production, the Merry Wives were above all an example of great ensemble theatre. The most prominent casting was of Mr and Mrs “Fluth” (in Shakespeare the “Fords”), namely Annelies Kupper – Munich’s favourite lyrical soprano of the day, singing roles from Mozart’s Countess via Verdi’s Desdemona to Wagner’s Elsa – and Karl Schmitt-Walter, perhaps the most versatile baritone of his generation, of stage and concert hall alike. Falstaff was sung by Max Proebstl, a perfect example of a singer whose commitment to a single ensemble shows up the pros and cons of today’s industry of the travelling stars. For a basso profondo such as he, possessing the characterizational abilities of a singer in the buffo genre, would enrich the everyday repertoire of any opera house. The second married pair on stage, sung by Lilian Benningsen and Kieth Engen, also offers proof of the virtues of a permanent ensemble, for their characterization of members of the old English bourgeoisie have profited from their experience of singing roles such as Princess Eboli or King Heinrich. As rivals for the hand of Anna (charmingly sung by Liselotte Fölser after the manner of Pamina) we find two brilliant tenors in the shape of Richard Holm (Fenton) and Paul Kuën (Junker Spärlich). And just like them both, the chorus of the Bavarian State Opera also guarantees what are the most important ingredients in a piece such as this (even without the accompanying visuals), namely a delight in humour and playfulness throughout.